Archives and emotions

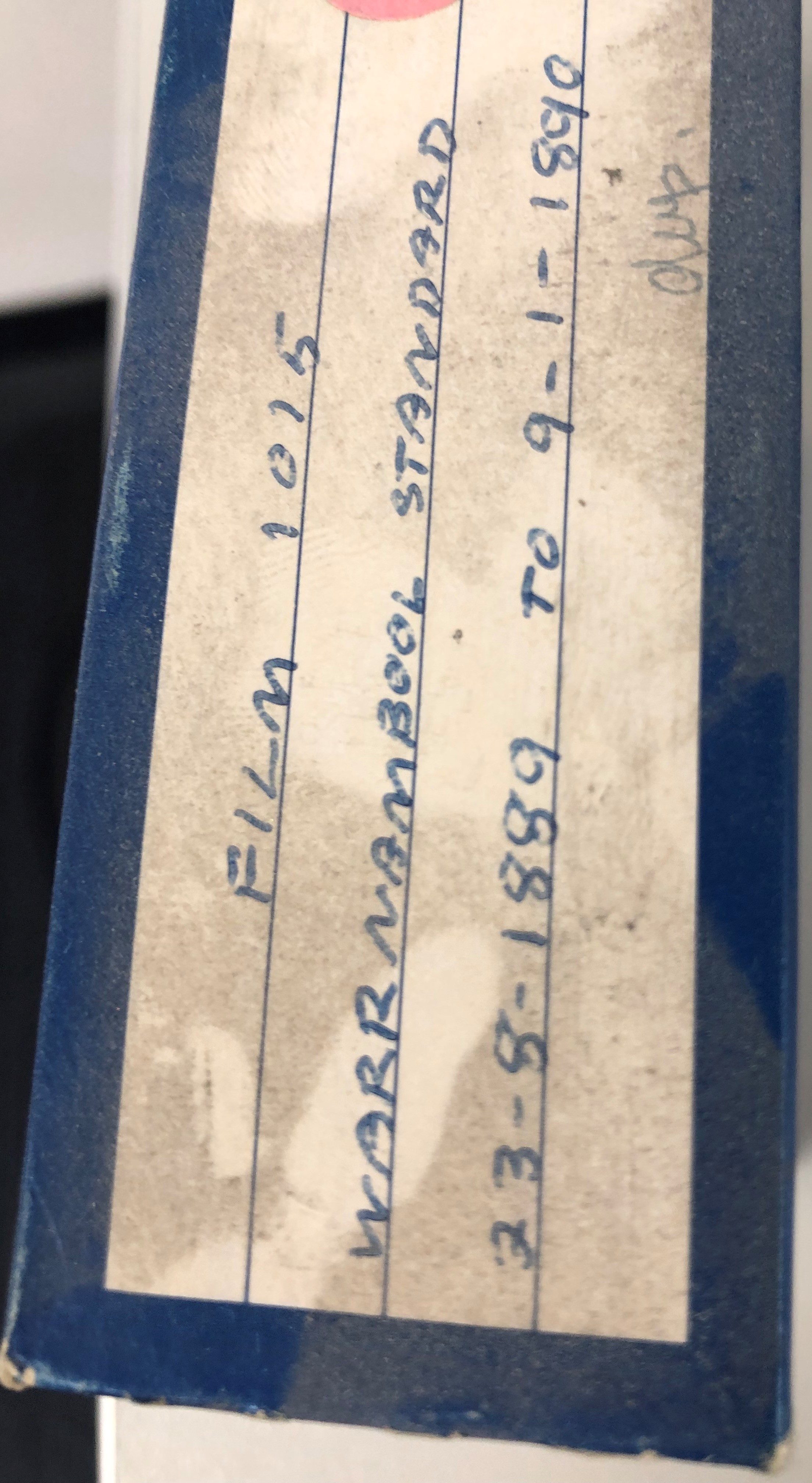

The dusty microfilm containers, in the image above, filled me with dread. I had been avoiding them for some time, hoping that TROVE would miraculously digitise the earlier years of the Warrnambool Standard and so prevent me having to scroll through frame after frame of these microfilm, as I sought any relevant information. The layer of dust accumulated on them in open wire baskets revealed I was not the only person who had avoided using these archival sources. Yet these dusty boxes eventually brought me great joy and insight – I found an article that transformed my research and led me to finding a petition, now the primary focus of my investigation. When I first took this photo, I was filled with dread and bemusement at the task I was about to undertake. When I look at it now, it happily reminds me of that ‘discovery’, of the thrill of finding something in the archives.

Historian Emily Robinson wrote of the affective experience of history some years ago now. She described this as a part of history little written about, but something that saw history as a profession, practice and academic discipline ‘withstand the challenges of post-structuralism and postmodernism’.[1] Robinson described engaging with archival documents as a ‘powerful’ affective experience, one that encompassed sight, smell and touch. Yet she argued that historians appeared to downplay or ignore writing about their ‘excitement’ about the past to avoid claims of ‘sentimentalism’.[2] Certainly I am not sure that my excitement espoused by my discovery will make it into any academic writing I do about this.

Robinson’s consideration of what it is that is alluring about archives and archival research and why historians shy away from writing about it covered a range of themes, including the importance of place and how artefacts and documents assist with ‘getting to know’ one’s historical subjects. However, Robinson’s focus of the affective experience of history was in particular relation to original archival documents. She noted digitisation of archival documents provides access to documents that may have been out of the physical reach of an historian, but argued they cannot replace the affective response an historian gets when seeing, touching, feeling and smelling the physical archival document.[3] There is something in this sentiment that I do agree with – the materiality in historical research can often be overlooked or downplayed. I have thrilled at seeing the actual letter in an archive that I have pored over online as I transcribed a digitised version. And the smell of archives, of the old paper and books turned and touched by various hands, is one that I find comfort in (this is also something that draws me to second-hand bookshops). Being able to pick up and hold, turn over and examine in detail a letter, a sketch or even an envelope adds to the engagement with the archive and the history it contains.

But is this affective experience only in relation to original documents in archives? In this case, I am not sure that finding the article that brought me so much joy in the actual, physical newspaper, would have necessarily increased my joy and experience. Whilst the article itself was illuminating and unexpected, I think it was the finding of the information, rather than the form of the archive that I responded to. In one sense, that the paper was from 1889, brings the realisation that having some form of digitised (or microfilmed) version is preferable, to ensure that we have access to a record, given the fragility of paper and capacity for ink to fade. This may also have been tempered by the fact that the original archival source was removed from direct human production, itself produced via printing machines after the text being set by human hand.

Tom Griffiths has written about historians venturing outside of the archives, of ‘walking’ the paths and sites of their archival subjects.[4] This is not only engaging with the materiality of the archive within the holding institution, but with the subject of the archive and the space in which the archive was possibly created, rather than the space in which it ended up. For Griffiths putting his boots on was an important part of understanding and engaging with his subject. Tiffany Shellam wrote about her familiarity and fondness for the Menang Noongar country in Western Australia she came to know through family holidays. She and her family would walk through and on this beautiful country year after year. In coming to this site as an historian researching and writing about early Menang Noongar and colonial settler meetings, she developed a different understanding of this country, one that was both familiar and unfamiliar to her as a non-Indigenous historian.[5] Where Robinson acknowledges the affective engagement of the archive within the holding institution, for historians such as Griffiths and Shellam, the space where the archive was created can augment understanding and appreciation of the archival content. Whilst my archival finding has been illuminating, I certainly feel that being able to head to Warrnambool and the surrounding district, to trace the path of the petition, would provide some understanding of distances travelled at the very least. Certainly it would do so in a tangible way that maps of the district have only done in a limited manner.

In her Quarterly Essay, ‘The History Question: Who Owns the Past?’, Inga Clendinnen noted the need for historians to keep their ‘emotions bridled by intellect.’ Doing so resulted in histories that were better able to understand lives, actions and cultures of past actors, to ‘penetrat[e] sensibilities other than their own.’ Clendinnen noted this was not an easy task. Reading through archives with detailed descriptions of torture, Clendinnen had ‘brandy-and-water at [her] elbow’ to help her through such difficult and challenging material.[6] I have at times wished for my own version of brandy and water reading through months of the Board for the Protection of Aborigines (BPA) meeting minutes. Instead I often opt for a time out by way of a brisk walk outside. I think this bridling of emotions is important, but it is not the same as the call to acknowledge the affective experience Robinson describes. Clendinnen was instructing us how to research as historians. When her intellect could no longer prevail over emotion Clendinnen would stop her work for the day. Clendinnen may not have agreed with Robinson’s thesis, but both historians acknowledged the emotional power of the archive.

Katie Barclay has written of both crying and laughing in an archive. She described the horror and distress she felt in ‘empathetic engagements’ with her subjects.[7] However, Barclay has been guided or possibly compelled by this emotional response to research and write about her historical subjects. She was interested in how historians’ ‘love of the dead becomes implicated’ in their work and posited that amongst the ethical obligations of historians as ‘witnesses and storytellers’ was giving voice to others. This demanded empathy and emotions and led to complex and multi-layered histories.[8] Whilst Barclay’s work examined the content of the archives, the subjects contained within, there is a affiliation between the affective response elicited by archival documents that Robinson described and the emotional responses to what is contained within those archival documents that Clendinnen and Barclay have considered. Both the documents and the content of the archives can elicit emotions within the historian.

Clendinnen noted the slow, challenging work of history. In thinking back to those dusty microfilm boxes, the image still evokes excitement within me. I had been researching for months and the finding of this article revealed a relationship between settlers and Aboriginal people not previously written about and opened up further avenues for research. It simultaneously consolidated all of the hard work previously undertaken and changed its focus. This archive has become important to me in a way that originally I had not perceived. I had little affectionate feeling toward it as I began researching. However now, emotion is included within my retelling of both the act of discovery and the content of my find with colleagues, as it is within their responses. These small boxes, covered in dust and containing scanned newspaper pages provoke an affective reaction in me.

[1] Robinson, Emily (2010) Touching the Void: Affective History and the Impossible, Rethinking History, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 503-520, p. 504.

[2] Ibid., pp. 504, 505.

[3] Ibid., pp. 509, 510.

[4] Tom Griffiths, The Art of Time Travel: Historians and their Craft, Black Inc, Melbourne, 2016, pp. 11-12.

[5] Tiffany Shellam, Shaking Hands on the Fringe: Negotiating the Aboriginal World at King George’s Sound, University of Western Australia Press, Crawley, W. A., 2009, pp. ix-xii.

[6] Inga Clendinnen (2006), ‘The History Question: Who Owns the Past?’, Quarterly Essay, vol. 23, pp. 1-72, p. 36.

[7] Katie Barclay (2018), ‘Falling in love with the dead’, Rethinking History, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 459-473, p. 460.

[8] Ibid., pp. 461, 464-465, 468-469.